THE RESEARCHER

|

|

|

|

“Integrating History”

Michael Woods didn’t know why, but in 1990, after living in Atlanta for several years, he bought a plane ticket to Oakland.

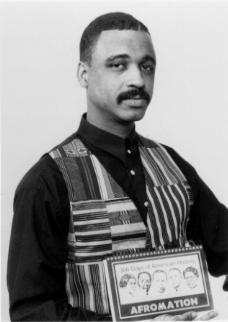

Woods looks back on that inexplicable act now as a sign. A calling. It was the beginning of a strange and varied journey that today finds him the author of a book on African-American history and the champion of a movement to integrate black history into American history.

“I’m not a writer,” Woods says. “The last letter I had written was when I was in the Navy in 1982. This was definitely uncharacteristic of me, especially to stick with something that long.”

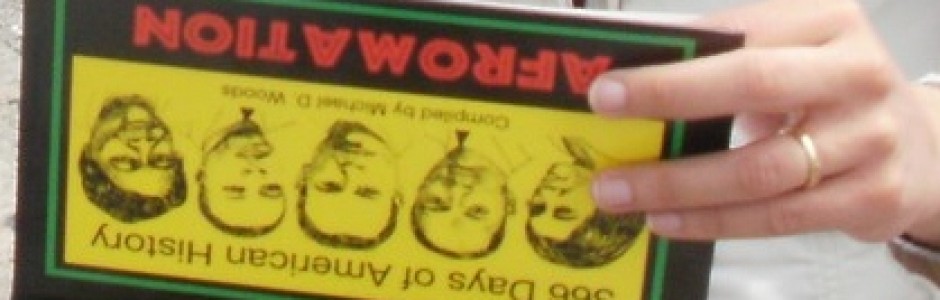

Yet, Woods is traveling around the country, promoting “Afromation: 366 Days of American History.” For each day of the year, the book provides a profile of an African American who’d made history and a short list of events that happened on that day. The back flap reads: “Too much history for just one month…”

Woods worked on the book for a year and has spent his own money, time and resources – whatever it takes – to get the word out.

Woods worked on the book for a year and has spent his own money, time and resources – whatever it takes – to get the word out.

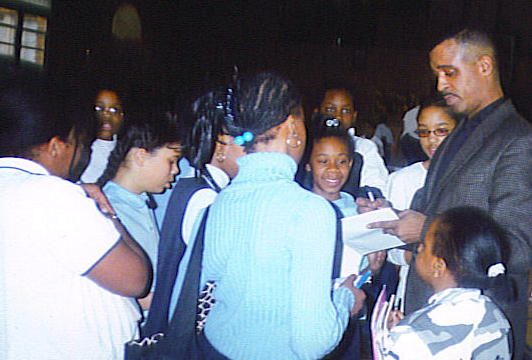

“The reaction has been overwhelmingly positive, from both black and white people,“ Woods says. “I’m just putting the facts out. The biggest response I’ve gotten is – ‘I didn’t know that. I didn’t know that happened.’”

Woods believes that the relegation of black history to one month has distorted the message and information

“That’s why I chose the format of history for every day. I’ve talked to teachers who said if they want to talk about someone black, they circle February,” he says. “I think Madame C.J. Walker should be discussed in marketing class and Charles Drew should be taught in biology – not off to the side in black history.”

(Walker was the country’s first self-made woman millionaire, making her money in hair products. Drew pioneered the collecting and drying of blood plasma for blood transfusions).

But I’ve gotten ahead of his story. In 1990, after a few months in Oakland, something happened. He stopped working, and in his words, he just stop caring about anything. It wasn’t drugs or alcohol. He soon found himself staying at a shelter in Richmond.

Because he had to leave the shelter after breakfast, he began visiting the Oakland Public Library. He read about Oakland’s history, about black history; he read newspapers from all over the country. And then almost as suddenly as he fell, he picked himself up. After an inspirational talk by a visitor at the shelter, he went to a social service agency and convinced the workers that if they gave him a one-way bus ticket to Seattle, he could get back on his feet.

“I’d been reading that Seattle was really booming,” he recalls. When he arrived, he had 25 cents. “But I had a job that night. I eventually got a permanent job. A place to stay. A car. I was back in society.”

Woods looks back at the curious stage of his life as a turning point. “I lost everything and found it all again in Oakland. I think I had to be pretty much stripped of everything, I had to go down to rock bottom, to be able to understand and deal with this book and what I’m trying to do,” he says. “Before, I was content to have my little 9 to 5 job. I didn’t care if I contributed to society as long as I had my little fun.”

The second crucial event in Woods’ journey took place in Seattle. A childhood friend read him a copy of a black history quiz that was circulating in his office.

“I always liked knowing facts. I got A’s in history. But I couldn’t answer anything on the quiz. All the years of schooling in what was supposedly a good education system. And I didn’t know anything.” Woods said his first reaction was anger. “All I knew about was slavery and Martin Luther King Jr. who was a great man. But it made me mad that I didn’t know the rest.”

The quiz sent him back to the library. For the first time in his life he developed hostility toward white people. “I was blaming white America. Why didn’t they teach me? Then when I talked to white Americans, I realized they didn’t know either. I felt it was my responsibility. And if I was doing it for my own benefit, then I should share it with other people.”

The quiz sent him back to the library. For the first time in his life he developed hostility toward white people. “I was blaming white America. Why didn’t they teach me? Then when I talked to white Americans, I realized they didn’t know either. I felt it was my responsibility. And if I was doing it for my own benefit, then I should share it with other people.”

He believes the overall ignorance of African-American historical contribu-tions hurts race relations. “I think white people look at us like a player on a Superbowl team who gets a ring, but never made a play. I’m here to say we did make a lot of plays and scored some touchdowns.”

The first printing of 15,000 books sold out, many of them sold out of the trunk of Woods’ car. He just raised the money for the second printing. Next, he plans a similar treatment of the worldwide contributions of people of African descent.

“All I want to do is integrate black history into history. It’s segregated now. And that’s not anyone’s fault, that’s just the way it is. What I’ve put out a book for all of us. It’s American history.”

Brenda Payton,

Oakland (CA) Tribune 1996